- Introduction

- Journal History of Isaac Sorensen

The History of Isaac Sorensen, Selections from a Personal Journal

I lived in Mendon in what my generation calls its golden age, 1880–1900. Pioneer conditions prevailed for most of this period, and the struggle for subsistence continued. Few modern conveniences were at hand until the mid-nineties, when headers, steam threshers, the Jackson Fork, fancy and white-top buggies and riding plows eased the burdens of the men who had begun dry farming. No household improvements cheered the women until a decade or so later when water works and electricity ushered in the modern era.

The Mendon people were poor but happy, in a period when one of the tenants of the United Order, unity and friendliness, drew the residents together in a congenial bond of common interests. Young people associated in groups of the same age, about thirty in a group. In the summer time we had frequent buggy rides, since the town was full of fine horses. It was also full of orchards, and all we needed for a good time was to meet under an apple tree and visit while we ate fruit that had not been visited by pests. In the many moonlit nights of summer we gathered on various lawns and sang or played games. Money was not half so important as was the hearty, friendly participation in all of our sports. Swimming was one. Blessed with radiant health and keen appetites, what mattered muddy roads or the never-ending chore of keeping the home fires burning. We know everybody’s dogs, horse, cows, chickens and sleighs, every room in every house, and called all the mothers, aunties. We were at home in any house.

During the winters merry sleigh bells jingled frequently on lively horses as big loads of us made the rides enjoyable. Coasting and skating were popular also, and many Saturdays were spent on the large fields of ice below town. Dancing, of course, was high on our list of pleasures. Our townsman H. T. Richards had built a dance hall of which we were proud and in which we danced with all the vigor of youth. In fact all of our friendly “sociables” in homes always open to us were occasions lively and pleasant.

We were close to pioneer days. We know all about feeding and milking cows, tending horses and hogs, and teaching calves to drink. When we were little we held skeins of yarn on our arms while our mothers rolled them into balls; helped to make starch and soap and smoke meat; and stripped sugar cane for the molasses, which was good on hot biscuits and better in the form of candy. Perhaps most of all we appreciated the roasts, puddings, pies and many other delicious viands our mothers drew from their ovens. We fed well in those days.

We went to school, attended all church organizations, sang in the choir and always defended the honor of our town, which changed little in the golden age. Henry Hughes and his counselors served for thirty years. Our Sunday school teachers worked for long periods. The Home Dramatic Company staged plays regularly. The Sweetens furnished organists and led a competent brass band. Our baseball team played a good brand of ball.

In this closely-knit town Isaac Sorensen served for twelve years as school trustee, fifty years as leader of the choir and forty years as Sunday School Superintendent. He was always a director of recreational activities. Interested in the town of his choice, he wrote a “History of Mendon,” a copy of which is in the files of the Utah State Historical Society. In 1903 he wrote a “Personal History” for his family, from which I have taken the following account. Modernization at times in spelling and grammar and sentence structure have in no wise changed the intent or meaning. Brackets show my words.1

![]()

![]()

1. A. N. Sorensen, one of Isaac's sons and Professor of English at the UAC, adapted this work for use in the Utah Historical Quarterly in the mid 1950's. (It can be found in Vol. 24.)

Journal History of Isaac Sorensen

Isaac Sorensen, son of Nicolai and Malena Olsen Sorensen, was born in the town of Hengerup in the district of Søro, Island of Sjælland, Denmark, February 24th, 1840.

My father was a farmer, also a wheelwright. [As a young man he loved music and for a time played violin in the Tivoli Orchestra of Copenhagen.] He had a farm of sixty acres, quite large for a place near to Copenhagen, on which he employed workmen and a dairymaid. In addition to his farm he had a shop in which he admitted apprentices to do such work as repairing wagons and other farm implements then in use, making coffins, new wagons, sleds, spinning wheels, etc. I was raised on the farm among the cows, horses, sheep and chickens and took much interest in the farm work. As a lad I herded cows, sheep and lambs, a rather tedious job, but necessary. Later I learned how to plow, harrow, mow hay with a scythe, and cradle wheat.

I started to school at age seven and went every other day until I was fourteen. I could read well before I started to school, and during my period of attendance I learned considerable history, wrote a fairly good hand, and could solve all ordinary problems in arithmetic. This was all the education I got. I was fond of amusements such as card playing, dancing, and baseball and participated in these sports with zest and relish.

When I was fourteen years of age, Latter-day Saint elders came into our town, and [the purpose and aims of life we had followed were radically changed]. Our whole family of devout Lutherans embraced the Gospel, but not all at once. The boys in the family were named Peter, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Christian and Henry. The girls’ names were Sophia, Christina, Marie, and Sena. Abraham and Isaac were baptized June 18th, 1855, father, mother, and Marie in September, Jacob and Christian and Christina soon after. Sena and Henry were not old enough then. Peter and Sophia were not converted yet. They lived away from our town and were exposed to the usual ridicule, which was by no means lacking in our neighborhood. Still, by degrees, the whole family working faithfully on them, they accepted the gospel and longed to go to Zion.

The time spent in Denmark after our conversion was the happiest of our lives. Father sold his place in the spring of 1856, but reserved the right to live in his workshop until April of 1857, when the family, excepting Sophia, left for Utah. Sophia and her husband, Andrew Andersen, promised to join them in Utah in 1858. [They kept their promise.] Andrew Andersen’s brother was working for father, had joined the church, and father added him to our family, twelve in all.

We bade farewell to uncles, cousins, aunts, friends, many of them, who seemed to feel very sorry for us, but we felt sorry for them who might, if they would, have believed our testimony and rejoiced in the glorious gospel, and been happy in leaving all for the same. We were happy in leaving the fatherland and traveling over seas, railroads, plains, rocky mountains, sandy hills in all kinds of weather, braving the danger of Indian attacks, buffalo herds and much else in a wild wilderness. We had great faith in the Lord and his prophets and inspired servants and on the 18th day of April 1857, said a last farewell to dear old Denmark. Arriving at Liverpool, England, we embarked on the sail ship Westmorland, and seven weeks later docked in the harbor of Philadelphia.

The tedium of crossing the ocean was relieved to some extent when we were not too seasick. We danced on the deck. The captain amused himself by throwing small cakes on the deck and watching youngsters scramble for them. The Saints on the ship were divided into four wards, each with a president. We held ward meetings, also general meetings. We often amused ourselves by watching the big fish and sea animals rolling in the water. Our worst trouble was that of appetite. Father was the only one of our family who could eat sea biscuits, so when we reached America we had lots of them. I think we sold them when we got ashore. In Philadelphia it was awkward for us to do our trading because we could not speak English, but we bought a number of things. I got a new suit of clothes.

We soon were on a train speeding west, and arrived in Iowa City seven or eight days after leaving Philadelphia, and were very busy picking out our outfits for crossing the plains. These outfits seemed wonderful to us, for many of us had never seen an ox before. The scenes to be witnessed the first few days are difficult to portray. You had to be there to appreciate them. It was indeed comical as well as pitiful. Driving oxen must, like everything else, be learned, and mastering the art took time. Sometimes the oxen would be piled up on top of each other in spite of the efforts of men on each side of them, for many of them had never been worked. However, we got along in a sure way. We left the yokes on until we reached Florence three weeks later. No one was hurt. There we found a handcart company and traveled with them most of the way to Utah, often camping with them for the night. We soon learned to yoke and drive our oxen and I was picking up English expressions. After nine or ten weeks we arrived in Salt Lake City on September 13th.

I was sick part of the way across the plains. I had chills and fever. In the hottest August days I lay in the wagon under the cover with a feather bed over me and would still shake. We saw many buffalo herds and sometimes killed a buffalo for meat. We were fortunate in having no stampedes. Other companies had them. We suffered no accidents, but we lost a number of oxen from poison alkali. Our best ox died and we had to buy a yoke of young oxen. Also we bought a cow that gave us milk.

Across Wyoming we often passed long freight wagon trains with ten yoke of oxen to a wagon. These were carrying provisions for the army on the way to Utah. Naturally we wondered what would happen to our people in Utah, and how we would figure in the outcome. But since we had braved much, but more because of our faith, we went on.

After arriving in Salt Lake City we moved south to Mill Creek, and wintered on Big Cottonwood. The first winter was so mild that I worked all winter husking corn. We hauled logs out of Mill Creek Canyon and built a house on a small farm we had rented.

On April 1st 1858 with a company of boys from Mill Creek and Salt Lake City, I went out into the mountains to guard against a U. S. Army that had come out to set the Mormons right. We went to Echo Canyon and from there to Lost Creek, where we made our camp and stayed for a month. We had no skirmishes with the soldiers but other companies burned the feed, drove off beef cattle and burned seventy-five provisions wagons on Sandy. Our company stood guard in half-night shifts. We were released at the end of the month and other boys from Mill Creek took our places.

If Uncle Sam had taken a little forethought and had sent a commission to Utah and investigated the charges before he sent an army out here, he would have kept his army at home. But the President and Congress listened to bad reports from judges who were sent east from here and on the strength of these false and wicked reports the army was sent. But it was, as it finally turned out, a blessing sent to the people of the valley, a beginning of prosperity, for much money was scattered among the people, good stores of merchandise were on sale, farmers sold grain and hay to the army, wood also, workmen made adobes, others worked on government buildings, and all in all, for a time, everybody had some money.

After I came back from Echo Canyon it was a short time before the move south commenced. This move included Salt Lake, Davis, Tooele, Weber, Box Elder and [Cache County] saints. All the counties south of Salt Lake were not asked to move. For some time before the move took place there was much talk of going far south into the White Mountains of Mexico. Even after their arduous trek to Utah, Mormons were willing to make a more hazardous journey to find liberty and peace. Nearly everyone was on hand to set fire to his hard earned home and go with the people of God wherever their lot might be cast. But this was not in the program. The saints had come to the tops of the mountains to build temples and make the wilderness blossom as the rose, and this move of the north counties south was all that was required of the people.

We went south with all our possessions in the way of household goods and what flour we had. It took several trips for me to get everything moved. We settled at Torrd [Pond] Town three miles south of Spanish Fork and some 70 miles from Salt Lake City. When all was moved down there I went back to Mill Creek to water the wheat and look after things. There was some one to look after most of the places, single-handed, no families, so thoroughly was Brigham Young’s counsel followed by his people. While on the place I was called to spend no little time in guarding Parley’s Canyon at the mouth.

In the later part of the summer I paid a visit to Torrd [Pond] Town, and while down there the word came to move back to our homes. This was happy news, and at once we made ready for our return. Soon again the roads were lined with teams and travelers wending their pleasant way north, instead of to the White Mountains. After our return I cut our wheat with a cradle, Christina bound it, and she and I hauled it to the stack. It was a fine stand of wheat, but more than half smut.

Father worked in Provo making spinning wheels for a man who cheated him out of most of his money. Later, this man apostatized and joined the foolish Morrisites who gathered on the Weber River. Father came back with me when I went for the last load. My brother Abraham was hired out to a man in Mill Creek. Peter was married and living in Provo. Christina was working in Salt Lake. Father’s money had all been spent in equipping his family and needy friends for the journey to Utah, the ship fares and the train fares.

Because I was the oldest boy at home, a good deal of responsibility rested on me at the age of eighteen, when we came back from the move. Father started a carpenter shop and made enough at that to get along during the winter of 1858–59. In the fall of 1858 my sister Sophia and her husband, Andrew Andersen, arrived in the valley and came out to Mill Creek. During this memorable winter I suffered the worst physical setbacks of by life. First I was scalded with boiling water down my left leg, which laid me up for several weeks. Next, while in Mill Creek canyon getting wood, it snowed heavily and in the morning we were covered with snow and lying in water. From that I contracted a severe cold that turned to pneumonia. I had faint hopes of recovering, but I did through the blessings of the gospel. The winter of 1858–59 was extremely hard and long. The people in their worshipping meetings often prayed for sunny weather to make spring work possible, but for us and many more who intended to scout new frontiers and make new homes it was still more desirable to have congenial weather for traveling. The move south had prevented the cutting of hay, and consequently, our oxen were reduced to poverty and needed good roads for traveling.

We had contemplated settling in the Provo Valley, now Heber, but the Hills' and others from Mill Creek voted for Cache Valley. Two Sorensen girls had married two Hill brothers, and so we decided upon Cache Valley. Peter was still in Provo, and as usual with our closely-knit family, we wanted him to go with us. I went to Provo on foot to tell him about our decision. I told him that, if he was willing he and I would take a wagon and two yoke of oxen, go to Cache Valley and start the home, and afterward return for the rest of the family. He agreed at once, and next day we started for Mill Creek.

The group leaving for Cache Valley included Alexander, James and William Hill, Andrew and Charles Shumway and families, Charles and Alfred Atkinson and families, Roger Luckham and wife, John Richards, Jr., Isaac and Peter Sorensen, Robert Sweeten, and Peter Larsen. We spent nine days on the trip to Cache Valley because of rains and the poor state of our oxen. It was in the second week of May that we reached the site where Mendon now stands. When we saw a clear stream of water we unyoked our poor oxen and turned them our to pasture on the abundant grass, which waved on all the hills. Lower down was fertile soil covered with wheat grass. Still lower and reaching to the river was a green section of meadow stretching for miles to the south and north. May flowers were in bloom, birds sang, the skies were blue in the clear sunshine, and I said in my heart “This is the place.” And so it turned out, for I lived out my life in Mendon, as did nearly all of the Sorensens’.

But the lateness of the season called for prompt action. We needed a crop of grain and after lunch the men walked up to the mountain and brought down enough material to make a three-corned drag or harrow for each family. Our oxen were too weak to pull a plow through the tough wheat grass. We had to put four yoke of oxen on a small plow. To do this we doubled with the Atkinson’s’. They plowed one day and we plowed the next, then we both harrowed the same day. Soon we had small fields of grain and we turned the water of the creek onto the thirsty soil.

On account of the danger of Indian raids, Peter Maughan asked the settlers to move to Wellsville, Maughan’s Fort, for the summer. We got out logs and in the fall built houses without lumber, excepting doors. All floors were of dirt. The houses in all new towns were built in forts, for reasons of protection. Two rows of houses had a six-rod street between them and a street behind them. Next came the corrals, then the stack yards and finally the gardens.

In the fall of 1859 the town at first called the North Settlement began to function. The Sorensen’s’ were moved from Mill Creek, Charles Bird came with a large family, seven or eight sons, most of them grown up. John Richards came with a large family. Ralph Forster and William Findlay and James G. Willie, [stalwarts in later history] came also. Andrew Andersen and wife, and Jasper Lemmon were there. So in it’s beginning, the fort had twenty-five families and several single persons. The houses were much alike. Logs for ten feet, a couple of windows, a lumber door, a N pitch roof thatched with willows and covered with soil, and of course, a big fireplace. We spent the first winter in old southern states style. No stoves of any kind were seen. We had bake skillets the same as we used in crossing the plains, and it is a fact that the bread thus cooked was sweeter than any that came out of an oven. One object was to get fires made, for matches were scarce. However, it was only a few steps to a neighbors and people were helpful. We met together and thanked the Lord for all his blessings.

For a few months Mendon was known as the North Settlement, but in a meeting held in November in the house of Charles Bird, apostles Orson Hyde and Ezra T. Benson organized the ward. When it was asked “By what name shall this settlement be known?” it was proposed that Elder Benson name it, then he said, “I will call it Mendon after the town in which I was born.” When the apostles asked whom we desired for our bishop, Sister Charles Atkinson nominated Andrew P. Shumway, who was sustained. [Democracy worked in Mendon.] At the same meeting I was chosen as music leader, a position from which I was never released. The ecclesiastical organization was simple in early times. There was a bishop without counselors, and next to him in authority was the president of the teachers quorum.

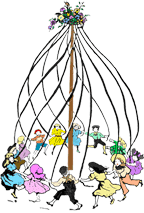

The winter of 1859–60 was a busy one. Mendon was a recognized ward and raised to a ward standard. We must have a meetinghouse, and we went out to get it. Some good logs were cut on the Mendon slopes, and hauled to Millville where there was a upright saw. Enough lumber for doors, window frames and a real floor was obtained. Men chopped logs in Millville Canyon in the cold of a hard winter, hauled them to Mendon, and by early spring a new church graced the fort. It was a welcome change from the cramped quarters of a private house. Religious services were enjoyed by devout persons seated on the hewed side of a log elevated to the proper level by sturdy props. These benches were moved around the edges of the hall to make space for dancers who moved willing feet to the call of the violin. Healthy, young and sociable they cast out thoughts of danger or difficulty and made merry. Happy in humble circumstances, they knew that Zion would become beautiful and be the glory of the earth.

In the spring of 1860 the Bakers, Woods and Gardners increased the population of Mendon, and took a very active part in ward affairs. A big piece of work was undertaken the same spring. Mendon residents knew that, in order to be safe, they should invite more settlers to their town. The problem was water, which could be had from Gardner Creek by building a dam. Since the minority to use the water could not do the work alone, it was considered fair to ask all the men in town to participate. The men worked every other day, which gave them a chance to take care of their individual problems. Plows, wheelbarrows and small scrapers were all the implements they had for the project, but with spirit and energy they completed the dam and the three-mile ditch in time for watering. All felt joyful; all was well, when to the sad disappointment of men and women the dam broke in a weak spot. Like all good pioneers the men brushed off their tragic loss, rounded their shoulders and began once more, this time with success. The old dam still stands.

Little has been said so far about the Indians. For a number of years they were a troublesome nuisance, because they were running our stock away and eating them. Although we spent much time on guard against them we never in Mendon had any battles with them. Instead of fighting them we did what Brigham Young always said to do. We fed them. Many a beef creature was brought for them, flour and other things they needed were given and by adopting this course many lives were saved. Peter Maughan, president of Cache Valley, was a loyal friend to the Indians. On July 24th, 1859, he and his people celebrated the great day. They built a bowery and served serviceberry pie, good bread butter and milk and great cuts of beef to Mendon and Wellsville people. After the whites had eaten, fifty Indians ate all there was left. When Peter Maughan died two hundred Indians in gala dress attended his funeral. It did not take us long to develop a sympathy for the Indians. We knew they were a remnant of the house of Joseph and sometime they would believe the gospel and do a great work in redeeming Zion. However, the settlers had much to contend with. Often it was necessary to go in groups, armed, to get timber. Once a group of young men Alexander Hill, Joseph Baker, William Hill, Bradford Bird and others chased a group of Indians who had stolen horses and cattle up into the Malad Valley. They exchanged shots with the Indians, but the redskins were in the cedars and had the advantage. After Bradford Bird was shot in the leg the posse returned to Mendon without the animals.

In the years following the winters were spent in dancing in the old log meetinghouse, and indeed many a good time was enjoyed with tallow candles to give light and Ira Ames doing wonders with his violin. After Ames, came Winslow Farr and then Dock Walker. Lars Larsen, called Fiddler Larsen, was greatly appreciated. It must not be supposed that the brethren and sisters forgot their church duties. They were on hand for all calls and labors and were hopeful and contented.

In those days money was rarely seen. Tickets for parties were bought with wheat or flour. We hauled our grain to Salt Lake for years and exchanged it for merchandise. Also, we took our grain to Brigham City to get our flour until mills were built in Cache County. Most of our income was from wheat we raised. There was no sale for butter or eggs, no market for stock except in exchange among ourselves. There was a demand for oxen. From two to three hundred bushels of wheat was considered a good crop in those days.

Time passed. Father had a carpenter shop and spent time in the winter making chairs, ax handles, ox yokes and other articles. There was ball playing in the spring of the year, and I took great pleasure in the game. In 1861 Mendon was two years old. The first team to leave Mendon for Omaha to bring back emigrants was driven by Amenzo Baker. He returned in the fall of 1861 with his four yoke of oxen and a load of Saints.

In that year one would find the spinning wheel turning from morning to night. After the yarn was spun, the next thing was to color it. Herbs and bark and curious mixtures were used. As time went on improvements were made until some rather creditable dress pattern were shown by the women— not broadcloth, but better than at first. The winter 1861–62 was long, hard, cold, wet, a test of patience and courage. Until the middle of January rain fell almost constantly. A cart loaded with wood would mire up on the bench. As to the houses, the dirt roofs leaked as constantly as the rain fell. Women and children sat in beds with umbrellas over them, and then couldn’t keep dry.

1862 was a late spring and an eventful one for me. I was called as a teamster to go to Omaha after emigrants. I left Mendon on April 29th. Our company waited in the Ogden bottom for eleven days for ferry boats to be built to cross the river in the highest water year known in Utah. All the tributaries of Green River were fearfully high and we had trouble with all of them and the Green. After this we made twenty-five miles a day. I encountered poison ivy on the Platte, and was a long time getting over it, but I got to Florence somehow. We stayed there for a week or more. It was a stirring sight to see the hundreds of tents on the rolling hills. We had brought flour from home and found ready buyers among traders and people aiming at California. I bought a fine Buffalo robe, which I brought home and used for many years.

We loaded our wagons to the bows. Eighteen persons with their luggage was the apportionment for each wagon. The return trip was made with efficiency. I had the luck of having an increase in my wagon. Mother and boy did first-rate. This family and another came with me to Mendon, but moved to Clarkston. The boy was named after me. I made two trips to Salt Lake after I got home. We did not do our threshing, of chaff piling, until the spring of 1863.

In the fall on 1862 a very sad event took place. James Graham and his son-in-law, Bishop Shumway, were down on Muddy River after willows, when Graham, coming to a thicket, was pounced upon by a fierce mother grizzly bear that killed him in a short time. Bishop Shumway, who was unarmed, drove back to the fort and called for help. All the men in the fort at the time drove down to the river to execute vengeance on the killer. She was hard to find, but at length was spotted in a tangled thicket. Dan Hill of Wellsville and James Hill of Mendon resolutely crawled into the thicket. The bear, seeing them, opened an angry mouth and came toward them. Dan Hill aimed his musket, which failed to go off. Calmly he shoved the barrel of his gun down the throat of the beast, which gave James Hill time to fire a true and killing bullet that finished off the bear. It was a frightful thing to look at good Brother Graham with his throat torn open and his chest and head mutilated. This is the only bear tragedy in the history of Mendon. It was often talked about, but James Hill would never admit [that he was a hero once] neither would Dan Hill. [It was only in the line of duty.]

In this year as in other years, not however every year, we were short of wheat for bread, and the only way we could, or did act was to go down to Mill Creek where we lived before we came to Cache Valley and borrow wheat and have it ground into flour. Then, after our next threshing, we would haul the same amount back again, and pay a peck on each bushel for interest. Even then we did not pay the men who lent the wheat because ours was smutty, and continued to be until we learned how to use vitrol.

In 1863, in the beginning of winter, a troop of soldiers from Camp Douglas, part of General O’Connor’s [Patrick Edward Connor] force, stayed in Mendon over night. They were on their way to the north end of the Valley to fight a band, or perhaps parts of several bands of Indians. They located the Indians on Battle Creek, east from Weston a few miles. The soldiers attached the Indians and killed most of them, including some chiefs. Some soldiers were killed and a considerable number were wounded. The weather was extremely cold, and when the same group of soldiers returned and stopped in Mendon, many had their feet frozen. Mendon people did all they could to aid the afflicted soldiers, who were suffering both from wounds and frozen feet. Chicken stew was the best food the Mendon women could produce. Some of the sisters were good nurses and won many thanks from the soldiers. This battle almost put an end to Indian depredations in Cache Valley. Still it was not safe for one family to live away from town, and the counsel was strongly against doing so. Mr. Thurston had a mill on Gardner Creek and lived by the mill with his family. One day, when the children came in from play, one was missing, a sweet little girl. At first the parents supposed the child had fallen into the millpond. A search of the pond brought no results. It developed that a man had seen two Indian squaws riding a pony with a shawl around the squaws. Then the family was convinced that the girl was stolen. Volunteers scoured the mountains but discovered no trace. The loss distracted the Thurston’s so completely that they moved to California.

1864 is a memorable year. The old fort was abandoned, the town surveyed and each family was allotted a homestead of one and a quarter acres. Four years of cramped living in the fort were enough, although the experience of such living brought the people together. Some of the residents moved their fort houses onto their new lots. Others built new log homes. We got logs from the canyon and built the house, father and mother died in. This house had hewed logs, dovetailed corners, nice door panels and lumber floor, a beginning of progression. In this year father and I raised the best crop we had produced. Father owned seventeen acres of farmland and twenty acres of hay land. I had a fifteen acre farm and some hay land. In the beginning of the settlement of the Valley this was the amount of land allotted, in order to make room for more settlers and more protection by number. We were kept busy during the summer making new corrals and stables. We also set out some apple trees, which did well. In the fort days peach culture was tried, but the trees froze. Berries, plums, apples and pears did well, and in a few years everybody had fruit. Watermelons also did well in the virgin soil.

The mines in Idaho and Montana were developing at this time. Many miners were located there and they depended on Utah for their breadstuffs. This demand could have been a blessing to us had we listened to the counsel of our leaders, which was for us to stay home and let the miners come here and make their purchases. In this way we could control the prices. But some were so anxious for quick gains that they started the shipping of grain and flour themselves, even hiring extra teams, and overstocked the market, thus bringing prices low. Some sustained heavy losses, scarcely having enough left to pay for the sacks after all expenses were met.

Through 1864–65 what at least at that time were considered improvements were in sight. Better log homes appeared, and some flowers here and there made places look more home like.

The fact of moving out of the fort influenced the spirit of improvement. Five years had changed the first log meeting house from a [first rater to a relic]. Mendon deserved a better church building, and by unanimous vote work began on the stone building in the west-central part of the public square. Almost completed in 1865 it got the finishing touches in 1866, and once again Mendon could match its meetinghouse with the best in the valley.

1866 was an eventful year. After a period of peace with the Indians, fears began to spread, possibly because of trouble with Blackhawk in central Utah. However this may be, our leaders became anxious about the safety of Cache Valley towns. Clarkston and Mendon were urged to move into larger towns. Clarkston did move to Smithfield but Mendon chose to remain at home.

The home militia was fully organized and private as well as general drills were set up. Mendon soldiers marched to Wellsville and were put through rigid muster or drill, once a week. The general muster for the Valley lasted three days, the first one being held on the bench where the Logan Temple now stands. Brigham Young was there to witness the maneuvers. A tall signal pole was set up on Temple Hill, from which signal flags could be seen on a clear day from Smithfield, Wellsville, Hyrum and Mendon. Carriers could carry the signals to places not able to see Logan. The militia was well organized, able men were officers, the regular men were well trained and in the event of an Indian attack we could defend our homes and families successfully. The Indians openly expressed resentment against the whites for helping the U.S. Soldiers who had defeated them at Battle Creek, and they wanted to give us trouble. Mendon had received orders either to increase their numbers or move. At a general town meeting the people decided to share part of their lands with newcomers rather than desert the homes they loved. At the same meeting the people decided that in order to make themselves more secure in case of an attack, they would build a strong stone wall around the new meetinghouse, with port holes at regular distances. All the women and children would be inside the meetinghouse while the men, with supplies of ammunition would guard the wall. Accordingly, all our men went to work with a will, some hauling rocks, others sand and clay, the rest laying the wall. We spent three weeks on this wall. After working three weeks on this wall right in July we began to worry about getting up our hay, which was more than ready. So the wall was left half completed and scythes began to mow the priceless hay. The way the sweat did roll off a fellow was a caution, for the July sun was hot. The brethren who had been factory workers in the Old World suffered much more than we who were experts with the scythe. Well, we got up our hay, but the wall was never finished. However, the work was not all wasted, for later when we put the "T" on the meetinghouse all the rock was used. We celebrated the Twenty-fourth in a very enjoyable manner in our new, convenient chapel.

Although the heavy Indian excitement of the forepart of the year had subsided, there was now on our hands another war— a grasshopper war. The hoppers came in myriads and destroyed the late oats. Fortunately, the wheat and early oats had been harvested. I was still a soldier in the horse company. General Ezra Taft Benson had ordered each horseman to have 300 rounds of ammunition, a gun, a revolver and a saddle. I paid thirty dollars for a gun, thrity-five for my pistol and the same for my saddle. I went to Clarkston and brought Andrew Andersen to Mendon where he has lived ever since.

1867 was an eventful year, for the hoppers had laid their eggs and they hatched readily in the spring. Nearly everybody in Mendon had some grain on hand, which was most convenient at this time. We wondered whether to sow our land or not, but Brigham Young said to sow it all. This was a wise decision, for tilling killed the eggs. My brother Peter left a few acres to summer fallow, and on these acres enough hoppers grew to eat nearly all of his grain. Father and I were more lucky. We raised 260 bushels.

This year was the greatest building year in the history of Mendon. About forty new rock houses were erected, and they matched the best in the Valley. In this year we put up father’s two-story house. We hauled four hundred perch of stone, and timber both for lumber and shingles. At the same time we were haying with scythes and harvesting with cradles. [Young men are capable of anything.]

1867 passed, as other years had, in a spiritual way. There was never any slacking up in that, perhaps everything did not work as well as it should have done but we tried. Spiritual and temporal works were always taught to be necessary. I always tried to do my part and had much satisfaction in the work. We now had a Sunday School completely organized. I was a teacher until I was chosen as superintendent.

1868. The great year in a financial way. Hoppers came flying in, but the wheat was too far along to be damaged much and we raised a fairly good crop. Oats and potatoes were damaged more. This was the railroad year. The U.P. and the C.P. were coming together. Workmen and teams were in demand and wages were $6.00 a day for men and $10.00 for man and team. I went out in the fall and worked on a rock job, blasting and hauling rock. During the winter much money was made by Mendon people who hauled hay and potatoes to the camps. Wheat brought $4.00 a bushel, hay and potatoes big prices. For us who had seen precious little money for nine years the jingle of coins was stimulating. When the gap between the railroads was completed we went out to see the Golden Spike driven in.

It would seem that, with so much money in circulation, improvements would be made correspondingly. But this was not the case. Whether it was because the people did not know how to use their money I cannot say, but there were few new wagons or harnesses in town.

1869 was a grasshopper year and we raised a half crop. The tide of progress had brought in mowing machines and grain reapers or droppers, which were a blessed change from the scythe and cradle scythe.

I had built a neat hewed log house with shingle roof, good floors and casings, and was ready for marriage to Mary Poulsen of Providence. We went to the Salt Lake Endowment House, not in a nice buggy but in a lumber wagon with no spring seat. I had a splendid team, Kate and John, and it took a good outfit to pass us. Father and mother went along with us and we had an enjoyable trip, one long to be remembered, when we traveled one hundred miles and are united for time and eternity. Our wedding day was celebrated two weeks after returning from Salt Lake. We were married on November 15th in good weather, and came back under fair skies. We had a big wedding dinner and a dance in the evening. Many of the guests stayed overnight. My good friend Peter Maughan came to the wedding and danced with vigor.

At the time of writing or compiling this history, 1903, we have eleven children all living. God has been good to us; our marriage has been entirely successful, for my wife is an exceptional woman.

I had been a school trustee for four years before 1869, and continued for eight more years. We assessed and collected taxes, and it was not always pleasant, but we got along pretty well in the old log-meeting house. I taught school for a time. We had to wait patiently for progress to inspire Mendon people to build a schoolhouse that our children deserved.

The Word of Wisdom was given to us in 1869 as a commandment, and all who would obey the commandment would receive the blessing promised. Many of the Saints were diligent in observing the law, but many were careless, in their habits and continued in their old ways. It is a noticeable fact that those who observed the law had more faith and were blessed of God. I had used coffee, tobacco and some whiskey, but when the law was given I threw my vices away and have never tasted them since.

1870, Indian troubles were over, railroads had come, improvements in farm machinery. Mendon City was incorporated this year, and received a charter. George Baker was the first mayor. The reason for the incorporation came from the feeling that a railroad station in town would invite saloons and gambling houses, and that in an incorporated town ordinances could be passed to prevent such nuisances.

The spring of 1870 came early and much wheat was sown, but hoppers reduced the crop one-half. The Utah Northern Railroad was started this year. The Utah Central from Salt Lake to Ogden was built the previous year. I worked on the Utah Northern from the beginning, because we could make big wages; that is, we thought we could. Our payments came mostly in stock, which declined in value terribly when the road, the rolling stock and equipment were sold to Jay Gould for $80,000. The return on my stock brought my pay to one dollar a day. However, the road was worth a good deal to us, and we finally saw a reward for our sacrifices. The railroad brought better prices for our grain, and also opened markets for butter and eggs. True to say, those who did not take part in the work were considered weak in the faith.

The Co-op Store, organized in 1869, was doing a good business in 1870. I had shares in it. The aim was to handle a considerable amount of merchandise at a profit of only 18% and pass on the benefits to the people. Housewives now could trade eggs and butter for groceries, and farmers could sell their products at home. We received more for our wheat in Mendon than we used to get after hauling it to Salt Lake, and furthermore, the prices we paid for goods were far below those of Salt Lake merchants who had to have 100% profit.

I took part in recreational activities such as theatrical and concerts and various musical groups.

In 1871 after putting in my crops as I always did in the spring at that time, I worked on the Utah Northern over at Dewyville until along in June when I came home to water my grain. This was a good year. Rain fell in June. My grain was a foot high and I believe it would have matured without watering.

At this time our grain was harvested with droppers. These machines would drop the bundles and then men and boys would bind them. We cut from four to seven acres a day.

Mendon had a sheep herd which was pastured on Three Mile Creek in the summer. We had from twenty to fifty sheep, which furnished wool for household needs. The herder was paid so much a head.

Peter Maughan, President of Cache Valley, and the first settler in the Valley, one of the staunchest pillars of this area, died in the spring of this year. He was greatly beloved by all, whites and reds. As proof of this there were at his funeral two hundred Indians in their very best dress, who followed his remains to the grave, and a long train of vehicles, so long you couldn’t see the end of it, drove to the cemetery. President Maughan was a careful leader, and saved more lives by his prudence than did any other leader in these parts. His plea was, feed them rather than fight them.

At this time our people were not without their troubles. We had as Supreme Judge of Utah, James B. McKean, who, in league with apostates and gentiles in Salt Lake, did all in his power to make trouble for the Mormons. He made unjust rulings, liberated criminals, and sanctioned many other wicked and unlawful things. He subjected Daniel H. Wells and others to imprisonment in Camp Douglas. An appeal from his rulings was made to the U. S. Supreme Court, which reversed McKean’s ruling. Brigham Young was imprisoned in his own house and guarded by soldiers. With some other brethren I went to Salt Lake during McKean’s administration and took out my citizenship papers. We stood the old man off very well.

In 1872 the Utah Northern reached Logan. A few months earlier, when it got to Mendon all the kiddies in town went up to the divide where a train stopped and gave them a ride to Mendon. There were dinners and dances in the settlements when the rails reached Logan. On to Franklin! Was the slogan now. But it was harder to get men to work than it had been. Men would say, “The big fish will eat the little ones.” But enough men volunteered to push the road to the terminus, Franklin.

I made a trip to Camas with a load of freight in September. It was a very cold September, snow fell and a fire was needed.

1873 was a beautiful spring for cropping and farmers enjoyed it. For quite a few years the people of the Valley had military drills, which lasted three days, and gave us a good time. Especially was it profitable for those who hated to get up in the morning, for at the call of the bugle all had to be on the ground to answer roll call. Governor Shaffer had issued an order to discontinue the drills several years before 1873, but the people here considered in necessary to show a front to the Indians, and did not obey it. Finis was written to it in 1873.

Winter opened in early November in 1874. It was a long, hard one, and feed ran out for many. Now President Brigham Young was always right, and always gave good advice. He told us to save our chaff for an emergency. I believed him and saved mine. So when the winter dragged on and people were in danger of losing their stock I let them have chaff and straw, even the straw off my sheds, and the stock lived, thin as they were. This spring the United Order was laid before the people in a serious way from St. George to Preston. A start was made, and in some places it continued for many years. Mendon took hold of it and all who wished to do so put their names and property in the order and never expected to get it back. From ten to twenty teams would go plowing together. The time of each worker was kept, and at the end of the year each man was paid according to the work he had done. I was one of the directors who had many things to do. Every man had care of his cows and horses on the open range.

The Order had this organization: a president, two vice–presidents, a secretary, an assistant secretary and a treasures. My experience in two years of this work I will never forget. Anyone who has labored in the spirit of the Order will know, to some extent, what United Order will be when it is finally established. Those who owned more land than others had no advantage, since the reward came from the number of days worked. I figure that I lost nothing in the venture.

Only about one third of Mendon’s people joined the Order. Those who refused to join did not lose any of their fellowship. It was a free will [democratic thing]. But it was plain to see, after two years, that the time was not yet ready for this order of things. But if the time should come, I think I would hail it with satisfaction. Before its close, the Order company worked in Paradise Canyon. They had the contract of hauling a large store of timber to Ogden Valley and from there to Ogden. Also they got out lumber and timber for building a cheese factory for the Order. The foundation was put in and much of the lumber got ready, but there it was left— never finished. The lumber was divided among the members of the Order later on.

1877, In this year the stakes of Zion were organized from St. George to Bear Lake. President Young traveled to all the places and accomplished this great task. He also organized wards or completed organizations. Up to this time the bishop of Mendon had served without counselors. Now Bishop Hughes was sustained as bishop, with Andrew Andersen and John Donaldson as counselors.

In this same year the temple in Logan was located. I attended the dedication of the foundation corners on the 2nd or 3rd of May, after a heavy snowstorm. Brigham Young said it was as good as a coat of manure, although it broke limbs off the fruit trees. It was a very interesting occasion and I was glad I saw the laying of the cornerstone of a great edifice on which I would be permitted to work.

After completing all these labors President Young died in August of 1877. His death struck a blow to his people such as has not been experienced since. He was dearly beloved by the Saints; had been their leader for thirty-three years, through the most trying scenes from Nauvoo to the present day. He was a man of great and varied ability— a financier, an organizer, a statesman, governor, president and was held in high repute by all. The Saints mourned with a sincere mourning. President George Q. Cannon was with him when he died, and was so deeply affected that he exclaimed, “What will we do now?” But it was whispered to him, “This is not man’s but God’s work.”1

![]()

![]()