The United Order In Mendon

On May 2, 1874, when Cache Valley was being instructed and organized in regard to the United Order in the meeting in Logan, Ralph Forster, acting church leader at Mendon, arose in the meeting and stated his ward’s thinking. He explained that Bishop Henry Hughes was away on a mission to England, and they were of the opinion to wait until his return before taking on this venture. This brought a sharp retort from Apostle Snow inquiring “if the Kingdom has to stop in Mendon” because the bishop was on a mission. This quickly moved Mendon into accepting and trying the new economic plan. In either May or June, Mendon organized their branch of the Order and elected a president, two vice presidents, a secretary, assistant secretary and a treasure. With these officers there were five additional directors chosen, making a total of eleven men directing this order. One of these directors noted a shortcoming of the United Order saying: “There was no real prescribed plan to work or to farm to.” But he declared they had a “Preamble.” Basically the local units were on their own, learning as they went, mostly by trial and error. “About one third” of the members of the ward joined which consisted of around twenty families. All who joined the United Order were rebaptized and some of the wording in this ritual was interesting and insightful. After saying the person was being baptized for the remission of their sins and “for the renewal of your covenants with God and your brethren, and for the observance of the rules of the holy United Order which have been said in your hearing,” concluding with a normal ending. Those joining consecrated all their economic property, meaning their farming or grazing land, their cattle and some other stock and the labor of each man, to the Mendon United Order in “good faith” never thinking they would possess this property again. They retained a stewardship over their city lots with their homes, their horses and ewes (female sheep). The organization was patterned on the St. George model with a written constitution with the preamble, platitudes, rules and provisions which were complied with except the promise to deal only with members of the order. The members of the U.O. were in the minority with twice their number not in the plan, perhaps being in the minority this may have been in their self interest. So they continued to deal and fellowship with those outside the order with only the thought that non-joiners may be weak in the faith. Thus one of the biggest incentives to join the order was never brought into play, ensuring they would remain in the smaller faction. In the end the United Order created two groups in the community and this division was called by a resident a “peculiar change,” causing frequent remarks that the U.O. couldn’t last.1

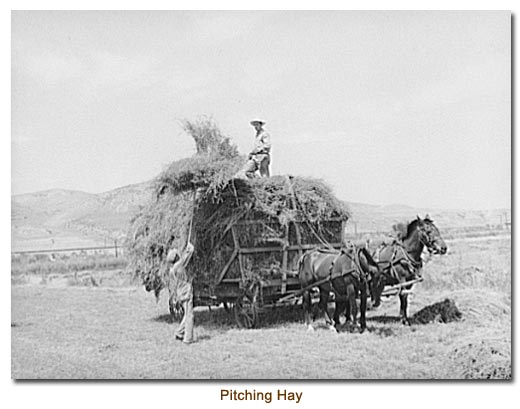

Their U.O. enterprise consisted of the co-op store and their lands and some animals. They were organized into two companies of ten men with a man supervising their work. First they set to plowing the land and because the previous winter had extended late in the spring, they had to wait until the land dried. The new cooperative way had an advantage; as soon as a piece of land was sufficiently dry, a group or two, quickly plowed the land and then sowed while in “good trim.” One participant in this activity noted it was a “novel sight” to see ten to twenty teams coming into town from their work at noon and night. One can only wonder if the same view was seen in the morning when the farmers took their teams to the assigned fields to begin work. Most likely when the person supervising the co-operative farming designated a certain field, he gave out a time to start this work. Did all arise early to complete their home tasks and chores to be able to move into a possession of workmen and teams going, or did some seem to be continually late and not showing the united spirit. At noon and night the work was called off at the same time so the movement back into Mendon was together by all in the working party. The return to work after the noon break, while possibly not as severe as the morning assemblage, could have shown a few stragglers frequently not marching to the same tune or time. Such differences in human nature, motivation and overall performance could have been seeds sown to undermine this united undertaking. The members of the Order continued to work together in cutting and putting up their hay crop. However, in regard to irrigating the crops each man watered the land he had turned over to the U.O. In the fall they harvested the crops and threshed the grain together. However, on the division of the crop they didn’t follow the plan but gave each farmer the grain raised on his former land. Still after a half a year in the system, there was some discontentment with a little chaffing along the line that the Order would break up when Bishop Hughes returned from his mission, he would “break the Golden calf in pieces.” On the other side, at least one saw benefits in the “oneness” with happiness, comfort and safety much like the people of Enoch or “the people of Nephi.” More than once President Brigham Young, Jr., presiding over Cache Valley, visited Mendon and congratulated the people’s efforts, saying he thought they “had it about right.”2

During the winter of 1874 -75, the members of Mendon United Order spent much time working in “Paradise Canyon” where they took a contract to haul lumber from the canyon sawmill over the ridge into Ogden Valley and on to Ogden. With their teams and wagons they would load the lumber and transport it to Ogden under the terms of their contract. The weather remained nice until New Year’s and made the hauling good; when the snow came, they had to choose times when they could haul the lumber. Apparently in payment for this lumber hauling they received both money and lumber. The lumber received in payment for this hauling was carried to Mendon where it was placed in storage. The Mendon branch of the U.O. began planning another cooperative enterprise of establishing a dairy (or cheese making facility) and the acquired lumber was to be used for this. In the early spring of 1875, the U.O. began preparing the ground and foundation for this new facility. A letter from Mendon to the Church newspaper dated January 24, 1875, reported the situation at Mendon as follows: “The United Order is progressing favorably. The majority of the people here are determined to carry it out. Some of the brethren have been off to the kanyon [sic – canyon], getting out lumber, to build a dairy which I think will be in operation sometime next summer, with brother Andrew Anderson superintendent.” This account by Alfred Gardner, a leading citizen of the town, was concise and appeared at the time to be a correct assessment.3 However, when spring farming commenced, the work on the proposed dairy foundation ceased and it never begam again.

In the fall of 1874, after the crops had been taken in and divided, the members of the Mendon U.O. made the final step to “fully” enter the new economic plan. They would work cooperatively in all facets—plowing, planting, haying, harvesting and threshing as they had the previous season, but this time each day’s work was recorded and credited to each member. This brought in the thorny issue of the value of each person’s effort, with concerns such as was there to be sameness or a difference between two farmers when one accomplished much more each day, or was the person herding the U.O.’s animals to receive the same credit as a man with a good team of horses doing heavy work, or should there be a difference between a person or persons doing the clerical recording of the various days work and everything associated with it, and those working in the fields. Was all labor to be equal no matter what, regardless of how it was done in quantity and quality. Questions that would have plagued even the wisdom of Solomon over the on-the-site practical workings of the economic plan. When the harvest and threshing was finished, an accounting would be made of all produced and labor credited with a calculation of the value of each day of labor. Whatever it amounted to, each would be awarded and paid in that produce. The farming season of 1875 proceeded and the two groups—one-third U.O. and two-thirds individual farmers—could see and estimate how each were doing in comparison to the other. In the summer of 1875 Bishop Hughes returned from his mission, and according to one of the directors, shortly after his return he had a “Dream”—“where it was shown unto him, that the tide was not yet high enough to float the ship, but after awhile it would be so and then he would take the breathern [sic – brethren], and with the rest of the Church work it successfully.” Apparently the discontentment with the United Order increased during the final farming season, and especially the final division of the agricultural goods. The director who kept a record of the activities in Mendon, stated that in this division, “The man with 25 Acres fared the same as the man with 5 Acres, or the man with none at all. . . . it was devided [sic –divided] . . . all according to the labor done.” In most of the failed United Orders, the most serious problem had been over the fair distribution of benefits, and in Mendon’s case this would have been the agricultural products raised. If in any way this division involved those considered indolent or slothful, it could make the situation grievous to unbearable. The accumulation of dislike for and problems of the United Order reached the point, according to the Mendon scribe, that the “Golden calf” (the new economic plan with all its promises) was broken “in pieces” (as all the pledged land and animals were returned to the original owners) as Mendon discontinued its United Order in the fall of 1875. Besides returning all the property, there was a division of lumber earned from the hauling contract. Mendon’s United Order existed for about eighteen months and one of the directors, Isaac Sorensen, gave a fitting epitaph for it stating: “. . . it was soon evident that the time had not Come for the establishment of the United Order.” Mendon was not alone in this as the same observer noted that the other settlements in Cache Valley had began working together like Mendon, also lasted for a “short duration.”4

According to Isaac Sorensen’s account, Mendon’s efforts with the United Order were short, covering just two farming seasons and disbanded completely in late 1875 when it proved unsatisfactory. While this was true there was a replacement of sorts that came into being. Likely the results of higher Church leaders, at stake and general levels, kept beating the U.O. drum incessantly at every conference, in Church periodicals and even the School of the Prophets, that the United Order had to be, was the only way, required, necessary and the Lord’s displeasure would come if rejected. To perhaps silence this constant sermonizing and ease some consciences, Mendon took a new tact and came up with its own version of a local co-operative project with local goals and objectives. In some way, never explained, the ward came to possess a parcel of 100 acres of land, which would be for the Mendon Ward, with the work open to the whole community on a voluntary basis. However, if pressure came from Church leaders, Mendon could refer to it as their united order. Apparently for over a year they preferred to call it their “co-operative farm.” It was a far cry from the original United Order, and not really a rejuvenated or re-directed U.O. Gone were the lofty goals and platitudes, promises, rules, regulations, rebaptisms, names affixed to an agreement or basic constitution or even stock in the venture. No regimentation, just a notice of work needed to be done in a co-operative way as had been done in Mendon since its founding. In mid-February of 1876, Bishop Henry Hughes was in Salt Lake City and he called at the offices of the Church newspaper, which gave his report of the situation in Mendon: “Matters generally prosperous in that settlement. A co-operative farm will be fenced and plowed in the Spring, preparatory to being sowed with wheat in the Fall, and early in the season a cheese factory will be established.”5 This community farm came to play a significant role in Mendon.

The bishop’s information on activities in Mendon was only three months after the formal-name affixed United Order in Mendon was abandoned. Although the U.O. members had disregarded the written provision of their Order that encouraged them to deal only with members of the United Order, still its existence created a division in the small ward. There had been some disenchantment within the membership of the Mendon United Order over how it functioned but it was insignificant compared with what followed. The larger issue and bone of contention was between a faction that thought there had to be a U.O.; it was absolutely necessary and required, and another group that did not want any part of that new economic arrangement with each side blaming the other for the situation that developed. For whatever reasons this split was not healed by the disbanding of the Order nor the bringing forth the co-operative farm, and so the contention and bad feelings continued for one year whereupon in December of 1876 “the United Order” issue remained one of the principal topics of discussion and friction among the people. At this point Bishop Hughes thought it “wisdom” to deviate from their usual custom of reserving Christmas Day for the amusement of the youngsters and instead have this special day for a public dinner for adults “as one family.” The ward received the bishop’s idea favorably, appointed a committee, and all the necessary arrangements made. Special care was taken that “none were forgotten or neglected” with each family receiving a personal invitation, especially the poor, to this special dinner. Wagon teams were assigned to carry those needing transportation to and from this Christmas dinner. When the time to eat arrived, one hundred and twenty-five persons sat down to this “one family” dinner, which carried over to taking food out to those, through sickness or other causes, who could not attend in person. After the meal and visiting there were five hours of dancing to cap off the activities with “all present feeling perfectly satisfied with the day’s doings” on this special day with a local theme of peace and unity as one family in Mendon. By deeds, spirit, mood and possibly some words, the residents began to forget the past and look to a better future than they had since the division began back in the spring of 1874. The youngsters were not forgotten, for two days later on Wednesday, December 28th, they had their Christmas celebration. All the children present were given a gift and in the evening a party with dancing and singing lasted till seven p.m. “when a herald announced the arrival of Santa Claus from the north, on his Shetland pony” and bringing “an abundance of apples and candies for the little folks.” The whole situation and the two celebrated occasions were described in a letter to the Church newspaper in which at the beginning the writer cited the continuing United Order discussions going on in Mendon. However, with the results of the peace and unity activities he concluded that it was “one of the happiest times ever enjoyed by the citizens of Mendon,” and ended it with his nom-de-plume or pseudonymous name or title, “U.O.”6 Undoubtedly he had a reason for this moniker, and, the tone and content of the letter suggests that the town’s recent division was a thing of the past and perhaps a more appropriate ending would have been U. M.—United Mendon.

No references to the United Order have been found for 1876 in Mendon by any source, and at the quarterly conference held in April of 1877, Bishop Hughes gave his oral report of his ward with no mention of it. Six months later at the quarterly conference in November in 1877, Bishop Hughes’ turn came after several bishops had mentioned the U.O. in their wards. Then he reported on Mendon stating in part according to the newspaper account: “They had a good store, connected with which was a butcher shop, doing a successful business; also a U.O. farm, from which was raised 150 bushels of wheat . . .the proceeds of this farm were devoted to Temple-building.”7 Conference reporting was a good time to bridge the semantics barrier, but in reality the community collectively farmed some land to assist them in their contributions to building temples much like missionary farms were later developed. Sixteen months later a letter dated from Mendon in mid-February of 1879, described the situation in the town as: “Mendon is a quiet little town, of between 90 and 100 families . . . . The community are [sic – is] industrious, frugal, and with scarcely an exception, farmers; each man sitting beneath his own vine and fig tree, owning the house he inhabits and the land he cultivates. The soil is very productive, and some of the best farms in the valley are contiguous to this settlement. Among these is one of 100 acres, owned by the entire settlement, whose yearly products are devoted to the building of the Logan Temple and the support of the Mendon Sabbath School.”8 Mendon had found what suited them best and had no intention of trying the archetypal model of the new economic plan a second time.

Mendon’s actions in regard to the formal United Order came when they decided it caused more problems than it resolved. The resultant “co-operative farm” was the choice by local leaders as far better for their needs and situation with far fewer side effects. Besides it provided some cover while the general Church was heavily promoting the United Order as the necessary economic plan. After Brigham Young’s death the new leaders were not as sure that the U.O. was the answer, and with the United Order’s high failure rate they moved to a less grand board of trade approach. At the same time in 1878 the new leaders began advising ward bishops to purchase community or ward farms for multiple purposes such as: providing work for the unemployed, a place for the poor being sustained by the local ward and a situation whereby new arrivals without any knowledge of agriculture could be trained and gain experience before starting their own farm.9 Mendon was ahead of the curve in moving in this direction. While this multi-purpose farm concept played out in a limited way, within a short time it was refined and heavily promoted that the each ward should have a missionary farm for the sustenance of families of missionaries while they were away preaching the gospel.10 In due time Mendon created their own missionary farm of forty acres located between Wellsville and Hyrum.11

In summation, Mendon was only a single branch in a massive concerted effort by Church leaders to establish the United Order in every Mormon branch and ward, and some 150 to 200 were created. The leaders preferred the St. George model with the pledging of all one’s economic property and labor to the Order in return for equivalent stock as it was initially believed this would create immediately the largest amount of capital to launch self-sustaining home manufacturing. With the heavy recruitment and being told this was the Lord’s plan, the end of time was near, plus a host of promised temporal and spiritual benefits, the movement resembled a tide sweeping over Mormon country. Then an un-welcomed trend came into being when the percentage of members joining the United Orders dropped from most, to three-fourths, to half, to one-third, and lower ever farther from the “whole people” concept.. Church leaders countered with even more promises, explanations and declarations that this was the way, the only way, absolutely a necessity and had to be because it had been revealed. However, this did not significantly change the sign up numbers and a worse problem developed. Some of the newly created Orders did little more than organize and elect directors, and a great many, estimated by scholars as about half, lasted only a year. Most of these Orders were based on the St. George model wherein those joining pledged or consecrated their property and labor to the order. In 1878 the St. George Order dissolved and only a very small number of this type of order remained functioning. The pledging or consecrating of property and labor was never popular. Even worse, the promised Heavenly order appeared more like earthly chaos as the practical workings of the plan produced serious disagreement plus a nightmare in determining the value of labor and keeping track or account of everything involved.12 The quick demise of the United Order in Mendon was on par with what was happening around it. With the United Order, the devil was definitely in the details, which the higher Church leaders avoided on the practical functioning aspects and left it all on the local stake presidents and bishops. With local control of the branches, there came a bewildering variety of United Order organizations with many seemingly custom designed or ruled, and that at Newton illustrates this as well as any.

![]()

![]()

1. Sorensen, History of Mendon, 79-82. Arrington, Brigham Young, 380, 393. Three years later and within three months of Young’s death he explained that in rebaptizing people into the United Order, only the basic words need to be spoken, “but if you want to put in anything else, you can do so.”

2. Sorensen, History of Mendon, 79-82.

3. Ibid, 82. Deseret News Weekly, Feb. 10, 1875.

4. Sorensen, History of Mendon, 81-83.

5. John R. Patrick, “The School of the Prophets: Its Development and Influence in Utah Territory,” (Master’s Thesis BYU, 1970), 107-109, 114-115, 136. Deseret News Weekly, Feb. 16, 1876.

6. Deseret News Weekly, Jan. 10, 1877.

7. Deseret News Weekly, April 18 and Nov. 14, 1877.

8. Ibid, March 5, 1879.

9. Deseret News Weekly, July 3, 1878.

10. Ibid., Dec. 24, 1884, May 3, 1886.

11. Ibid., June 13, 1895.

12. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 330-331.